I. INTRODUCTION

Eighteen years have elapsed since I became a site-oriented sculptor. that time I have confirmed my need to design works that enhance rather than interfere with the original site. 1968, when I created cuteway to the Wind (Fig. l), a 50-foot freestanding concrete sculpture, to represent Mexico on the Olympic highway [1] , I became obsessed with the idea of relating this work to its immediate surroundings. This meant studying the approach to the site on foot and by car or by bus; the light during the different seasons; the scale in relation to trees and buildings; and the likelihood of change, either through the addition of new constructions around the site or through the growth of trees in the surrounding area.

construction for station 17 of the “Route of Friendship” for the 1968 Olympic games in Mexico City.

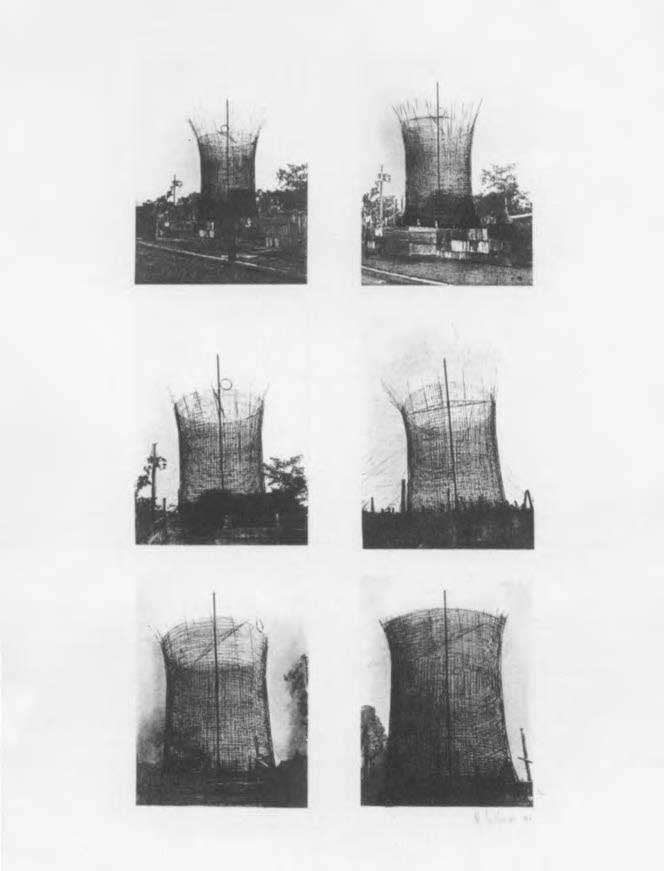

It was during the actual construction of Gateway to the Wind that the idea of transparency came to me. I watched the careful network of steel grids going up prior to the spraying of concrete onto its understructure and was fascinated with the language of subtle precision achieved by the metal rebars which looked like a misty image of my original proposal. When the concrete was sprayed on, slowly hiding the very soul of the piece, the sculpture began to look like what I had originally intended, but at the same time it began to lose something vital. It no longer reflected what was beyond, but rather concealed it and made the viewer look frontally at the object I had created: a perfect large-scale rendering of my original model painted in blue and green-a solid, monumental sculpture.

My ego was intact but my spirit was broken.

The tenuous ethereal image that had vibrated so briefly against the vivid blue sky and the dark green pastures beyond had had so much impact on me, had moved me so profoundly, that I had felt secure in the knowledge that if the structure looked so marvellous, then the final stages would look even better. I watched the sprayed concrete going on like the gooey icing on a cake, and 1 never left the site until the surface had been smoothed and patterned into its great parallel lines. I worked on the colours and saw them being applied, giving even greater definition and clarity to the sculpture. I saw it finished and was pleased: my first monumental work was up and ready; it looked majestic and even imposing in its rural surroundings. Gateway to the Wind, the seventeenth station on the Olympic highway, was about to be inaugurated alongside its 17 partners from 17 foreign countries [2] .

I had created my first urban sculpture and through it had achieved the first inklings of a deeper insight into myself: I did not want to stand out, I wanted to merge with nature; I did not nee background-I wanted to be back-ground; I did not want to interfere with but wanted to enhance what was already there. It was not a question of being self-effacing but of joining my creativity to that of the environment on its own terms, much as light, colour, shadows, mist and rainbows do, in their own time and in their own way, affecting the onlooker, altering perceptions, transforming surfaces and causing variations of depth, illusion and heightened perspective. Although it would appear that I express myself more like a painter, I admit to interfering threedimensionally with space.

An example of all this is what happens to me when I see a building, a church or a monument that is covered temporarily by scaffolding. Although its very temporality would appear to make the scaffolding unnoteworthy, the delicate tracery that extends the well-known silhouettes of public monuments into the skyline not only creates a visual stimulus but alters the solid mass beneath and completely transforms one’s perspective of it, dramatizing and making us aware of our own previous knowledge of what was there before.

Such is the reasoning behind my search for transparency, if reasons are necessary to make the point that scaffolding has always held a fascination for me and inspired me, just as a forest of tall trees has or the endless columns of ancient Mexico or the temples in Greece.

To create a rhythmic interruption of space-repetitive sequences-to sculpt the light, to use space as iridescent volume rather than solid matter: this is the subject of my present inspiration and the object of my research. But in this article I will emphasize the technical aspects in order to explain how I am beginning to achieve monumental seethrough works that do not involve high risk or excessive cost nor require constant maintenance.

II. WORKING METHODS

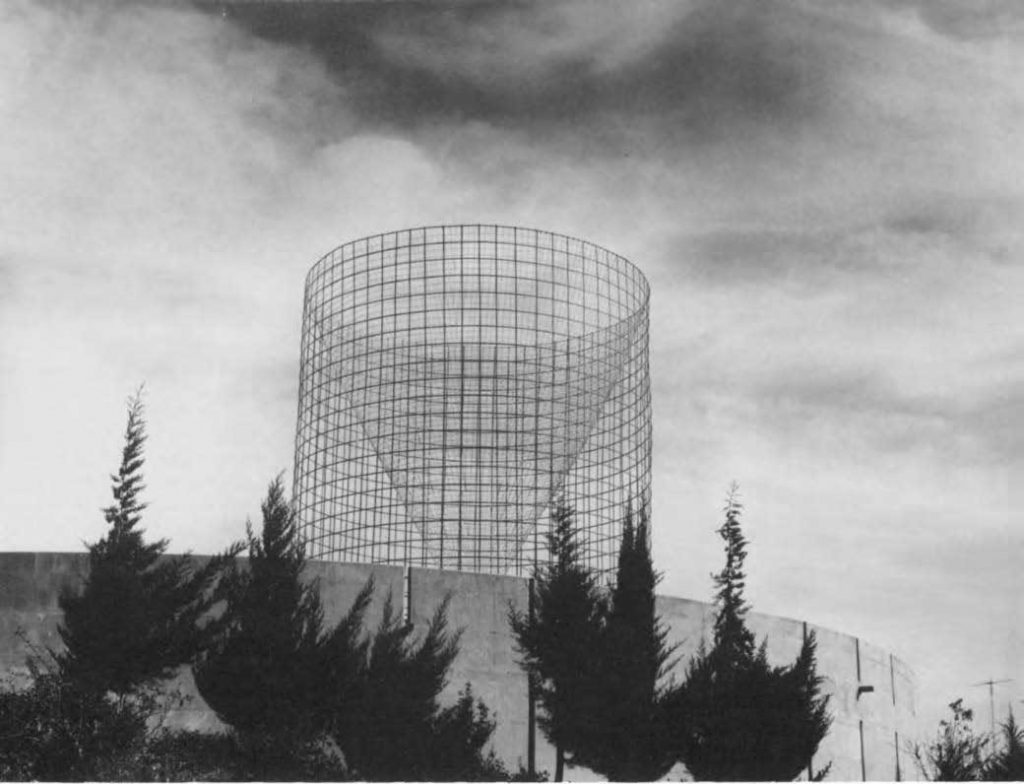

When making ephemeral environments that last a short time, whether indoors or outdoors, I most often use steel mesh in varying degrees of open grid. My permanent outdoor pieces present the biggest problem because they must be built on the actual site and, given the diaphanous, ethereal quality I seek, must nevertheless be tough enough to withstand climbers and vandals. The largescale sculpture entitled The Great Cone (Fig. 2), which I recently built in the city of Jerusalem, was designed to stand on a hill using a low, round cistern as a base. The vivid sky, a cluster of trees and the silhouette of the new housing area in East Talpiot were to be highlighted by my piece. I wanted the mesh cone inside the mesh cylinder to be like a vertical sun clock, changing colour as the sun curved over it. The lightness of the sculpture was a favourable asset when it came to dealing with the city engineers; however, it became a problem when dealing with the insurance experts who worried about the liability caused by adventurous climbers. Since ‘Keep Off signs and barbed wire were considered unsuitable we finally came up with a delightfully appropriate solution: cacti planted in profusion around the base of the cistern would create a natural and perfectly acceptable barrier against prospective climbers and, incidentally, vandals. The cone is bright yellow, the cylinder red; the effect is luminescent orange, depending on the time of the day.

Chinese red.

III. COLOUR

A factor that is absolutely basic to my nature is the use of colour. Colour certainly requires maintenance, but if a good quality paint is applied over a layer of anticorrosive paint, the work may not need a fresh coat for 3 years.

Painting requires scaffolding, an expensive item to consider when keeping costs at a minimum; thus the feasibility of climbing the piece in safety without having to build scaffolds is a factor I also take into consideration. My sculptures are their own scaffolds, in a manner of speaking.

Some colours, I have found, are better than others: blues and greens do not seem to last as long as yellows, reds and oranges. Also, colour applied to steel and iron is far more lasting than colour applied to concrete, especially if the steel and iron have gone through a sandblasting process to provide a grainy surface, to which paint clings more readily than to a polished one.

IV. EPHEMERAL WORKS

Steel mesh of varying calibers is available in rolls at large hardware stores. Wire cutters and a hefty pair of gloves are all I need for large-scale installations, which I usually build as ‘artist in residence’ together with my students.

To achieve translucent, gossamer qualities, I use three calibers of mesh which are then painted in three grades ofdiminishing colours. For outdoors, against sky or green environments, I prefer hot colours like yellows, oranges and reds; however, if I am on an arid site, I may use cool colours like lime and forest green and vivid blue.

A couple of years ago on a university campus in Los Angeles, California, I led a workshop for whose site I chose an alley flanked by giant oak trees. Here we made 20 cylinders that echoed the height and width of the oaks. These were then spaced to echo the two rows of oaks trees (Fig. 3). The effect was startling: because the columns were made of three concentric cylinders of mesh in diminishing thicknesses and painted in hot colours, they looked like shafts of light. In daylight, with the sun piercing the foliage of the trees and casting shadows on the cylinders they became almost transparent, difficult to focus the eye upon. At night, however, they were invisible and on two occasions were knocked down by an aggressive team of young football players cavorting late at night. I might add that I took some delightful photographs of the recumbent cylinders which reminded me of felled autumnal trees. The piece was called Autumn Came Full Summer.

V. WORKING METHODS USING PHOTOCOPYING

As I am often given specific sites to work with, I have found the need to photograph them to keep every detail in mind. For many years I projected my colour slides of the sites and made notes from them for the eventual piece. Today I photograph the site in black and white and make prints. I then blow up these prints using photocopying equipment onto a thin paper [3] in as light a shade as possible so that the site is printed lightly on the drawing paper and my background is ready to work with.

Another method I use is to tear from a magazine a page that has a site that appeals to me-for instance a street flanked by trees and a monument that I want to replace with a work of my own. I use a pale grey marker to block out the monument. (The felt-tip pen absorbs the printer’s ink and blanks out the image.) From here I can proceed in one of two ways: I can draw in my own proposal directly, photocopy the altered page onto artist’s paper and overdraw until I achieve the desired results; or I can photocopy the original image minus the monument onto high-quality paper and draw my proposal directly onto the fresh sheet.

It is no secret that a hot iron is effective when used to transfer photocopied images onto white paper, although it is a difficult process requiring patience and skill. It is even less of a secret that certain felt-tip pens in light colours will obliterate printer’s inks such as those used in lesser quality glossy magazines. What I had todiscover was how to erase sections on the photocopies I had made where I wanted to clear the space for the drawing in of my proposed sculpture. Here the felt-tip pen technique worked after using a soft eraser, and I have become skilled at this process. The drawings in which I use this system look like engravings (Fig. 4), whereas my free-style pastel drawings reflect more the ways I see the sculpture, how colours change at different times of day and during the seasons of the year. I include drawings that use both these methods in the exhibitions that accompany the inaugurations of my public sculptures. The drawings are invaluable to me as an expression of my work and help the public understand the many facets I go through, such as my initial reaction to the site, imagining how it might look and evaluating the various viewing angles in terms of light, distance and approach. They are not working drawings but entirely emotional ones which describe the passing of time around an object.

VI. ENVIRONMENTAL DRAWINGS

When I produce drawings for the sake of drawings and am not being inspired by one of my site-specific works, I either invent an environment or photograph one that has caught my fancy enough to inspire an attempt to transform, redefine or place it into an entirely different context. This normally occurs when I travel and have no place to work. I am greatly attracted to ruins, whether ancient or recent. My fantasy conjures up vivid images of what they might have signified, and I use my camera to take various angle shots of them in their surroundings. Using a wide-angle lens, I overexpose the images by letting in more light than is normally prescribed for a good photograph. I do not wish to pick up any detail, only a misty reminder, rather in the manner of a hasty sketch. Using the amplified photcopying printing methods I described earlier, I elaborate on the barely suggested forms on first class paper in soft pencil; then as I define the forms more sharply, I use china ink, pastels or Conti. crayons. The resulting work transforms the ancient or industrial remnants into sharply defined sculptural elements that read as drawings of found objects in ideal settings.

This, then, is the essence of my search: to redesign by transforming or extending what is already there, to seek inspiration within the given time, and genius loci or spirit of the place.

VII. FABRICATING RIGID PAPER

My latest work, a total environment for a private office, is a sequence of drawings on steel mesh squares. After many experiments with a professional in handmade paper, we came up with an ideal solution for my requirements.

Casting the paper pulp onto a fine grid of steel mesh cut into rectangles of 25 by 30 inches, we leave a I-inch margin of mesh like a frame around the paper. This gives me the possibility of hanging them onto each other with miniature hooks and hanging the whole mural in any space merely by suspending it from a steel rod near the ceiling like a Chinese scroll.

This particular work entitled Wish You Were Here is like a giant postcard of a seascape cut into squares and blown up to room size. Each square is an interrupted sequence of the next one-interrupted by the steel mesh frames that extend from one drawing to the other.

The paper is pierced with random holes producing an ethereal quality and transparency. It also permits more hooks for paper cutouts such as boats, fish or sails, for this is a marine scene depicting clouds, horizon and water. It is flanked on one side by another giant postcard of sleet and rain and on the other by a violent sunset. I use pastels, Conti. crayons and gallons of fixative of crystal-clear lacquer.

The main characters are undoubtedly the people in the room.